I keep thinking about the art that has surfaced over the past few months. It is an unrelenting series of works that emerge from crisis and not comfort, traveling freely while their makers do not. It all arrives to me from what feels like everywhere all at once. I know where my body is, yet my seeing is unmoored. It is terrifying to realize that art no longer demands my presence, only my attention. I hover over paintings from Minnesota, zoom in on photographs from Los Angeles protests, and watch impromptu diversion tactics unfold as performance pieces on streets within nearly every state, sped up to twice their time. We all do. And I understand that these works are connected, even when they appear formally and geographically unrelated, because they are all being made under the pressure of war and political collapse. One thing that lingers for me is not only what these artists are creating, but how they are being asked to survive while making it. These works emerge from what often feels like an empty promise of support, forcing me to question what structures actually exist for artists in times of crisis. There are few systems in place that allow artists to endure, let alone thrive. It feels less accurate to say we are living inside a failed dream than to admit that what we are witnessing is not breakdown but an alarming success, the predictable outcome of institutions built to extract cultural value without assuming responsibility for those who produce it.

So from these thoughts, I have spent the last few months turning toward the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a history that feels both under-discussed and deliberately allowed to fade. I am not invested in mastering its bureaucracy as much as I am invested in sitting with the fact that, at one point, America named artists as necessary to collective life. Considering the now, this feels bold even though through my research I can only conclude that the administration was frankly inadequate. It is difficult to take seriously a system that recognizes what is so desperately needed only in moments of uncontestable crisis. The need existed long before, and it will remain long after. But it is precisely within this inadequacy that I believe possibility opens. The WPA’s short life reminds us that care does not have to be perfect to be structural. If there is anything to carry forward, it is this quiet recognition that progress was once understood as inseparable from visual culture. And that the artist was not ornamental but essential, regardless of political alignment or aesthetic position. For some this may read as radical, even though countless non-Western civilizations have long insisted on the same truth. In all, my writing does not seek a return to that structure, but names the necessity of reimagining such a commitment now. Especially in a world where crisis is constant and the future is actively shaped by what we choose to protect, what we allow to erode, and what our digital systems are already deciding to forget.

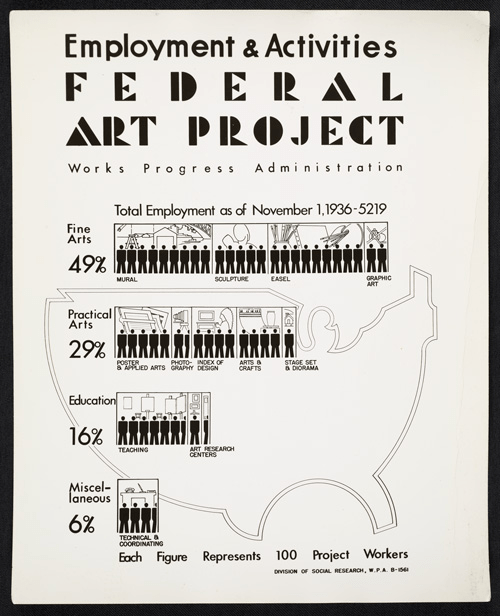

In July 1939, as the Great Depression (1929–1939) neared its end, the federal government made a deliberate intervention into the question of collective responsibility. The Works Progress Administration (WPA), established in 1935 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, was conceived not as charity but as an employment program designed to stabilize everyday life through work. Within this framework, the Federal Art Project (FAP) emerged as one of the most ambitious efforts to support artists through public funding in United States history. It followed earlier short-lived efforts like the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP, 1933–1934) but expanded significantly in scope and ambition, offering employment to tens of thousands of artists across disciplines: painters and sculptors, musicians and dancers, writers, photographers, and actors. As FAP Director Holger Cahill explained in Art for the Millions: Essays from the 1930’s by Artists and Administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project (1973), “The resources for art in America depend upon the creative experience stored up in its art traditions, upon the knowledge and talent of its living artists and the opportunities provided for them, but most of all upon opportunities provided for the people as a whole to participate in the experience of art.” Rather than appealing to sentiment or exception, the WPA treated artistic labor as work that warranted public investment. In doing so, it repositioned cultural production within the economic and social conditions that sustain democratic life.

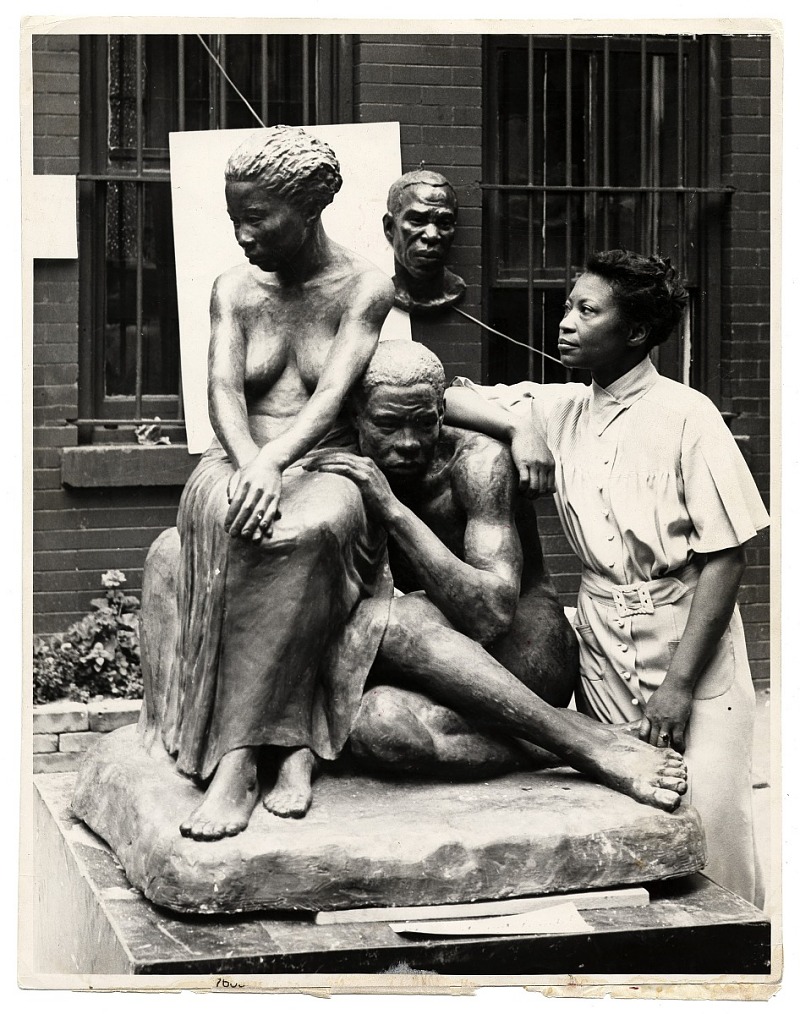

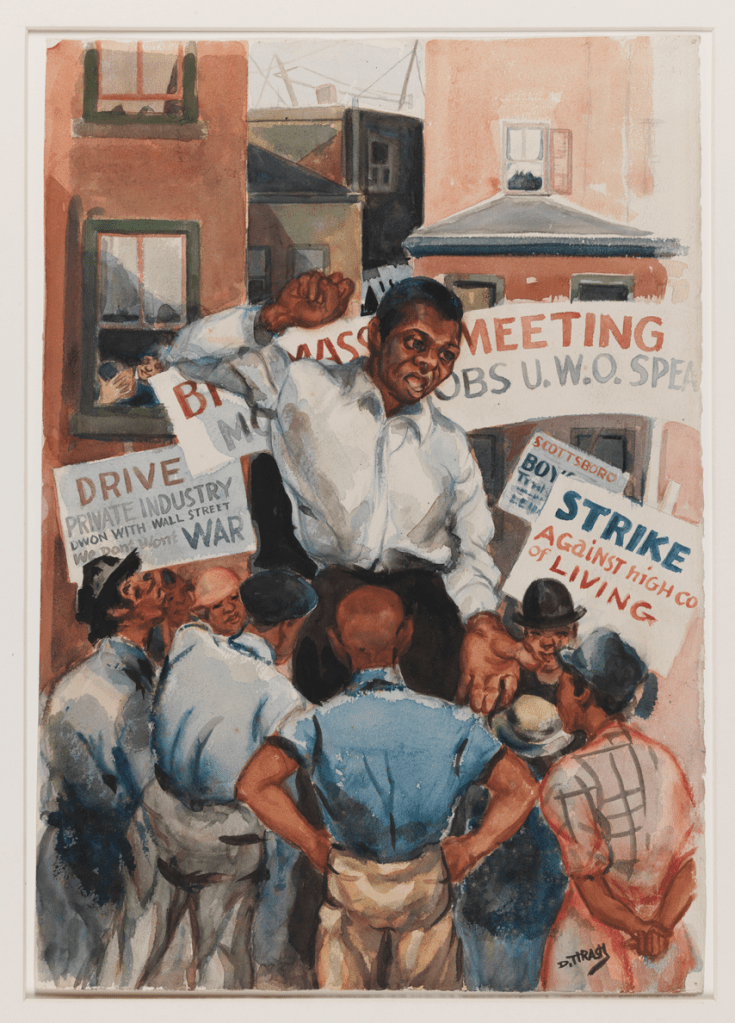

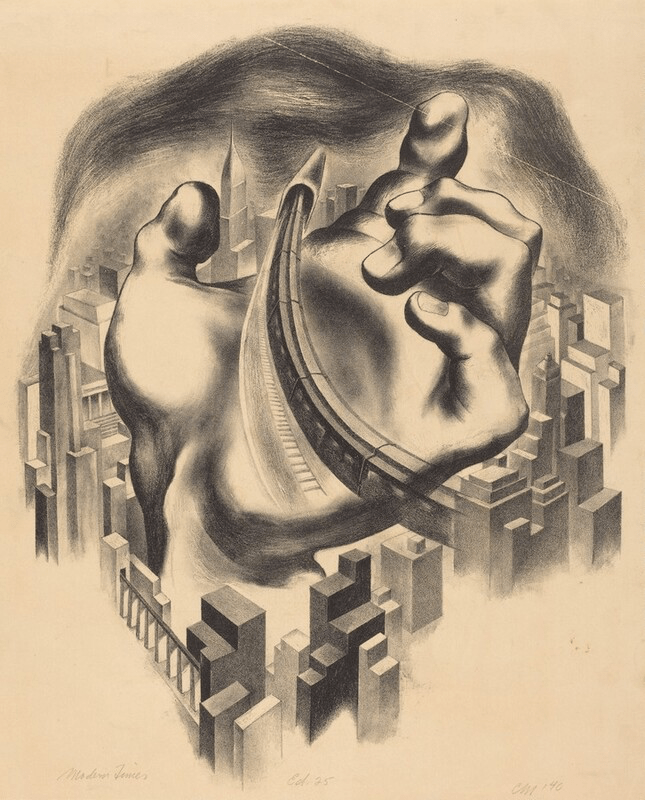

Structurally, the Federal Arts Project organized itself around four central tenets: art education, the creation of art, art as a foundation of community life, and archaeological, technical, and theoretical research. These principles formed a basic but expansive framework whose logic was deceptively simple: begin with a program and allow the work to flow from the people. In doing so, the FAP helped lay the groundwork for what would later be understood as the emergence of American art as a dominant cultural force in the postwar period. The program officially ended in June 1943, not without consequence and not without offering a moment of profound creative relief. Artists such as Dox Thrash, Henry Gottlieb, Ad Reinhardt, Augusta Savage, and countless others emerged as thoughtful products, or more accurately, necessary alumni of this system. Their work bears the imprint of what becomes possible when survival and creation are briefly allowed to coexist. The WPA/FAP did not merely produce objects, but conditions. Though temporary these conditions were transformative and sustained artistic life rather than deferring it by offering a living wage and a place to create. What followed was a sense of purpose that cannot be replicated.

Yet even as the Federal Art Project embodied a democratic spirit, if such a spirit can fully exist within capitalist infrastructures, its organization was rudimentary at best. Bureaucratic oversight often constrained experimentation, folding creative labor into narrow definitions of usefulness and public value. Importantly, this constraint was not uniform. As Mary Curran (1885–1978), Director of the Philadelphia branch of the FAP from 1935 to 1938, recalls in Dox Thrash: An African American Master Printmaker Discovered, “Every effort has been made to allow the artist to continue working freely and with no sense of restriction or regulation.” Unlike other branches, artists in Philadelphia were not subjected to rigid production quotas or strict timekeeping systems. Instead, the program relied on an honor system that balanced supervision with trust, requiring artists to be present in the field or studio during set working hours while preserving a sense of autonomy. This localized flexibility reveals that the FAP was not a singular structure, but a series of negotiated environments shaped by those who administered it. Support, in this sense, was both enabling and stifling. The system sustained artists while simultaneously disciplining them, revealing a tension that continues to haunt contemporary models of cultural funding: care that comes with conditions, relief that is never entirely free, and creativity that must ultimately correspond to monetary justification.

What remains integral, however, is that there was a moment when the government could look at the artist directly and, even without full agreement, support the act of creation itself. Federal funding sought to contain art by positioning artistic labor alongside the work of everyday Americans, offering salaries and commissions that recognized artists as workers within a national economic project. The program required accountability and massive oversight, which undoubtedly shaped material production. And yet, it was understood that art itself could never be fully contained. When the people are angry, the art will be politicized. And when the people are happy, the art will still be political. Creation is always political. But at the very least, it was understood to be necessary, and for contemporaries, it mattered more that this work was made in America.

Art remains one of the most potent forms of communication we have, second only to the spoken word itself. In all its multiple forms, it is capable of translating not only urgency but also care, and systems of survival across generations and communities. And yet, the federal structures that once recognized this power no longer exist. There is no longer a central entity responsible for sustaining creative labor at scale, no shared funding system that treats art as necessary work and public good, and increasingly, no trusted platform to document the hyper-transitional nature of art and visual culture emerging from our contemporary moment. The closest federal successors, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), offer grants and fellowships, but not widespread employment. Whereas the WPA treated artists as workers essential to society, the NEA and NEH treat artists as cultural contributors whose value is often measured by output, prestige, and alignment with institutional priorities. There is little room for the experimental, the revolutionary or the unrestricted creativity that emerges when basic labor and survival are supported. What the WPA/FAP once offered, however imperfectly, was a recognition that artists require material conditions in order to produce meaning, especially in moments of crisis. Its absence today leaves a void that shapes not only what is made, but who is able to make it, and under what conditions.

History has shown us what art looks like in times of war. We know how artists respond to scarcity, violence, and rupture. We also know how governments turn to culture in moments of crisis, and how quickly that support recedes once the crisis passes. What the WPA and Federal Art Project clarified, and what the present moment further complicates, is that artists do not simply respond to crises. They absorb them. The difference between those working with material support and those laboring with almost nothing is written into the textures of practice itself: in the layered washes of printmaking, the density of charcoal on paper, the archival rigor of studio notes, and the reach of improvisation into form. Survival and making are inseparable. Again and again, creativity bears the responsibility to both witness what is and imagine otherwise.

Yet the conditions shaping artistic absorption today are no longer defined solely by material scarcity or political rupture. They are increasingly structured by speed, by technological mediation, and by the erosion of material continuity itself. We are living in a moment in which visual culture no longer has the shelter of history. Images move faster than we can hold them, faster than meaning can settle. Past, present, and future collapse into a single, restless now. Futurists anticipated this condition as acceleration, but they could not fully account for its cultural cost: a visual field in which orientation is perpetually deferred, and interpretation becomes an act of navigation rather than understanding. What history has not yet supplied is a legible account of art produced under conditions in which crisis is not exceptional but continuous, automated, and structurally indifferent to human presence. So the question is not whether artists will continue to make work. They always do. Nor is it simply how they will survive. Creativity has always outlived the structures meant to contain it. To give form to the world is one of the oldest human impulses, a language older than institutions and more durable than the systems we are taught to trust as permanent. But what happens when those systems no longer hold? When cultural labor is called essential but left unsupported? When the very qualities that make us human are dismissed as inefficient?

In a world shaped by these conditions, the artist is rarely erased outright. More often, they are gradually separated from relation itself. Art comes to be understood as product rather than process, a shift long anticipated by the institutional logic of the white cube gallery. The artist is no longer apprehended as a life sustained through community, but as an individual output assessed by speed, visibility, and return. What disappears in this transformation is not only economic security. It is the web of care that makes making possible at all.

This is why returning to the Works Progress Administration matters. Not as a practice of nostalgia, or even as an idyllic model to be replicated, but as a reminder that there was a time when artistic labor was understood as public infrastructure. The WPA cannot answer the conditions we face now. Technology has shifted too dramatically. Power has reorganized itself through so many overlapping forms that even the media once tasked with holding it accountable has been weakened. Still, this history offers something vital. It helps us imagine systems in which care and creation are not treated as secondary, but as foundational. It reminds us that making need not be a solitary struggle, but a shared responsibility, held in common.

To be clear, there is no single framework waiting to be named. Collective care cannot be imagined in isolation. It has to be practiced together, shaped through use, revised through listening. Still, if artists are to endure, creation must move beyond representation and toward structure. Toward networks, habits, and ways of holding one another that allow creative labor to persist even as institutions and markets turn toward efficiency, militarization, and automation. This kind of structure does not promise stability. It depends instead on adaptability, on redundancy, on shared responsibility, and at times on complete invisibility. It may only emerge on the precipice of extinction. Even so, it would remain a living system. One that protects paper, paint, clay, and even touch not out of nostalgia, but because these materials remain necessary for thinking, for remembering, and for resisting erasure. And within such a system, studios, schools, and community spaces would return to their original intentions, not as sites of extraction or acceleration, but as places of sustained encounter. They would resist being reduced to pipelines for productivity, branding, or career optimization. Instead, they would function as nodes of relation, connected through shared resources, mentorship, and the open circulation of tools and knowledge. Even now, many artists can’t survive through funding alone, but through the constant networks of care that refuse the premise that creativity is disposable.

If we take this seriously, interdependence is bound to become visible. Necessary even. Making becomes instructional as much as expressive. A way of teaching us how to live together. In this sense, structure is not architectural. It is a living scaffold: a set of relations that sustains material practice, preserves connection, and defends the human capacity to create against systems designed to render it redundant. Such a structure offers no guarantee of permanence. It keeps creativity in motion. In this way, the Works Progress Administration appears not as a model to be recovered, but as a historical proof that artistic labor can be held collectively, even as the present demands new forms of coordination and refusal. What remains is not a single future to be secured, but a set of possible worlds still awaiting construction.

PUBLIC ACCESS

WPA Posters at the Library of Congress

African American Artists and the New Deal Art Projects: Opportunity, Access, and Community by Mary Ann Calo

The Federal Art Project in Washington State by Eleanor Mahoney

Two Artists of the Great Depression by Nayeon Park and Sabrina Bekirova

WPA Posters: Art for the Common Good by Arpie Gennetian

What We Can Learn from the Brief Period When the Government Employed Artists by Tess Thackara

Leave a comment